| Density | ||

| [ Images | PDF ] | ||

| Density is a property of matter that is defined as the ratio between the mass and the volume of a solid, fluid, or gas (i.e., Density = Mass/Volume). Mass is a fundamental physical property because it is conserved. When comparing fluids, however, mass is not a very useful quantity. We may have a lot of one fluid and little of the other, yet it is the one that is denser that will sink below the less dense fluid, regardless of their relative amounts. Thus for fluids we are interested in the mass per unit volume, that is, the density. |

|

|

What can density tell us about the ocean and the life within it?

Oceanographers use density to identify water masses and trace their movement in ocean basins. The density of water is primarily determined by its temperature and salinity (the effect due to pressure is relatively small). Water masses are layered according to their densities, with the densest water (usually both cold and salty) at the bottom and least dense water at the top (usually both warm and fresh). You have probably experienced a similar phenomenon while swimming in the ocean or in a temperate lake in the summer: floating on the warm surface, you can feel the temperature drop when your toes reach deeper waters.

|

||

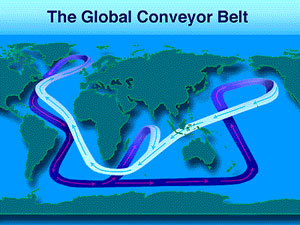

Stratification refers to the layering of fluids according to their density. The atmosphere, oceans, and the Earth are stratified. Changes in fluid density result in a vertical motion of fluid termed convection. This important process drives circulation in the ocean, atmosphere, and Earth’s interior. Density driven ocean circulation is referred to as thermohaline (from Latin terms for "heat" and "salt") circulation. The global ocean conveyer belt is one example of thermohaline circulation (depicted at left, image from NASA). This idealized model depicts how the world's system of ocean currents distributes vast quantities of heat around the world oceans. Blue arrows on white paths indicate warm surface currents driven by the wind. Red arrows on blue paths indicate the deep ocean circulation affected by differences in temperature, salinity, and density.

|

||

In highly stratified conditions, it is difficult to move parcels of fluids either up or down. This is because of the large restoring force (i.e., buoyancy) pushes them back to their "original" density level. Stratification has important implications for ocean primary production. Under highly stratified conditions, a lack of vertical mixing can prevent the delivery of key nutrients to phytoplankton at the ocean surface. Conversely, well mixed ocean conditions can help bring nutrients from depth to the ocean surface, fueling ocean productivity. (This image compares highly stratified fluids at left with a well mixed fluid at right.)

Density is also the property that is used to determine if an organism or an inert particle will float or sink in a fluid. Marine organisms have devised different strategies to adjust their density so they can remain in a favorable part of the water column. For example, some phytoplankton have gas vacuoles (i.e., chambers) that help them decrease their density. Likewise, marine mammals can expand and contract their lung volume while ascending or descending in the water column. Without such adaptions, organisms would need to expend more energy fighting buoyancy forces to reach other depths.

How might this workshop benefit my students?

The eight activities depicted below were designed to introduce students to the concept of density (solids and fluids) by making their own density measurements, making predictions on whether objects will float and sink and testing their predictions. Full details and explanations of stations are available by clicking here (2.7 MB PDF file).

|

|

|

|

Click on any image to see a larger version |

|||

|

|

|

|